Back to Back 25 - Mummies Don't Hurt Their Own Children

Contrasting Monstrous-Feminine Motherhoods of Male Nightmare

The Brood (1979) - writer/director David Cronenberg

Possession (1981) - writer/director Andrzej Żuławski

Genre: Marital breakup-breakdown body-horror. Cold War pre-apocalyptic eldritch absurdist fantasy (Żuławski)

Recommended snack: Grilled cow placenta in brahok sauce washed down with kumis, an alcoholic beverage made from fermented mare's milk.

Recommended musical interlude: "We Share Our Mother's Health" by The Knife [Trentmøller Remix]

Robbie Redpill, Mansplainer-In-Chief, made a recent pronouncement on this important matter on his Podcast Real Alphas and the Chicks that Adore Them:

I'm told there are still women among us who choose to have offspring out of their V-hole, like it was 1978 or something. Look, ladies, I hate to get your pretty little heads all in a tizzy, but the V-hole isn't a respectable baby conduit any more. It's reserved for funtimes, and as a place to smuggle A-grade chang from Colombia so you can afford to rent a tiny space under the stairs in a nice neighbourhood.

Real cool dudettes spawn monstrous abominations from birth sacs that sprout spontaneously from their skin out of feelings of rage and self-loathing, capiche? Parthenogenetic reproduction is the new normal, baby, and legacy obstetrics is for loser-lasses who never got the memo. All other things being equal, hate-spawned monstrous offspring are a helluva lot cheaper to deliver and rear than the old-style bouncing baby.

Horror, true body horror, comes to us out of a nexus of desire, fear, revulsion at the messy innards that are under the skin, and the haunting awareness that this icky mass of gloop is subject to decay and corruption. Julia Kristeva calls all this good stuff abjection and in her seminal book of poetical philosophy-psychology The Power of Horror: An Essay on Abjection (1980) - by coincidence or synchronicity published bang in the middle of today's movie selection - gets into the hows and the whys from Biblical times to the present. Because back in the days of the Ancient Hebrews there was even then the potential for maternal body horror:

The tender and delicate woman among you, which would not adventure to set the sole of her foot upon the ground for delicateness and tenderness, her eye shall be evil toward the husband of her bosom, and toward her son, and toward her daughter, and toward her young one that cometh out from between her feet, and toward her children which she shall bear: for she shall eat them.

Deuteronomy 28: 56-57

Kristeva notes that among the ickiness that is categorized as "unclean" in Leviticus - leprosy, foul sores, tumours - is childbirth, when a woman will be considered taboo for a period of time. "To purify herself, the mother must provide a burnt offering and a sin offering. Thus, on her part, there is impurity, defilement, blood, and purifying sacrifice."

What's so bad about childbirth, why is it aligned with the defilement of leprosy? Kristeva puts on her Freudian hat to psychoanalyse an answer: "Evocation of the maternal body and childbirth induces the image of birth as a violent act of expulsion through which the nascent body tears itself away from the matter of the maternal insides." [Kristeva, p101].

Whether or not we subscribe the Kristeva's post-Freudian explanation of why childbirth and maternity has so many taboos associated with it in early society, it makes fertile ground - in the Freudian spirit, pun fully intended- for speculation about body horror and the female body, which is where we're going today. Barbara Creed definitely thinks so, and leans heavily on Kristeva in her discussion on Cronenberg's The Brood as well as James Cameron's Aliens (1985) and other 80s horror films based around a "monstrous-feminine" image, in her study The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis (1993).

To kick off with a thesis, we might begin in contrasting Robert Altman's Images (1972) with The Brood. Both are made by a male director and portray a woman in the process of breakdown of self, the classic Gothic theme of the fragmentation of the ego. For reasons we can't detail here, but which I've discussed more extensively elsewhere, Altman really doesn't succeed in making an effective film out of this material.

I suspect the failure is really to do with his reluctance to get down and dirty with the immaculate Susannah Yorke in that film; ultimately he respects women too much to take them off their pedestal and scuff up their radiance with the messy stuff of Gothic horror. Alex Garland's Men (2022) is a similar case; all the body horror, especially the icky obstetrics, befalls the titular men/man of the film and the agency-less Jessie Buckley is left to gasp and retch ladylike at the horrid stuff ensuing.

Female directors like Julia Ducornau, Karyn Kusama or Claire Denis don't share this delicate reluctance. Their characters have agency and choose to fragment themselves in the way that a horror protagonist like Dr Jekyll traditionally does. The good doctor drinks his gloop and transforms into Hyde; similarly Alexia in Titane (2021) chooses to smash her face and become the blunt-nosed boy Adrien.

The same is true, in one way at least, with male directors who are either transiently or permanently at war with women, who are temporary or inveterate misogynists. They may not always give agency to their female protagonists, as Cronenberg does not with his brood mother who neither chooses to spawn her brood nor consciously controls what they do. But they will have no reticence about getting their women in the messy stuff, and that's where things get interesting in the Gothic sense.

So the thesis would be that only those filmmakers who are prepared to take female characters down into the thick soup of dissolved consciousness, the ghastly horror of bodily decay and transformation, are the ones that will be able to say something interesting, whether out of empathy or contempt. So a man who is at war with women, as are the directors of the films on offer today, will reveal something important, even if it's not what he intended to reveal. And whatever happens, if the disgust is real, the horror will be sincere and powerful.

The Brood starts with the screechy discordant notes of violins (scored by Howard Shore) that lets you know that this is a 1970s horror film. Oliver Reed is busy abusing a younger man who seems to be his son. They sit face-to-face; the young man is on the verge of tears as Reed repeatedly calls him weak. Then we're off to the races:

You're weak. It probably would have been better for you to have been born a girl... You see weakness is more acceptable in a girl, Michelle. Oh, I'm sorry, I mean Mike.

The intimate conversation cuts to long shot and there are rows of people seated watching this confrontation. A duffel-coated man walks in and sits high up at the back. Reed is now on a roll, abusing Mike his son as only Ollie Reed could. Classical British acting, you really can't beat it when it comes to contemptuous disdain.

The camera tracks around him, the lighting making the most of his scarred cruel face. We've situated ourselves now, it's a theatre performance, one of these Theatre of Cruelty things where the characters do their utmost to reduce their opposite numbers to miserable heaps of tears. Sure enough, young Mike starts to break down, confess that he loves Daddy but hates him too.

As Mike breaks down totally, his father embraces him. We see the performance from up in the back of the theatre as the lights go out. But there's no applause. The man sitting next to duffel-coat whispers admiringly "Wow, the man's a genius." What kind of crap drama group is this?

As the theatregoers move outside to the bus, duffel-coat walks upstairs where he finds "Guest Room G-5" and goes in to find a little girl. "Candy?" he calls. The little girl, about 7 or 8, does not seem exactly overjoyed to see him. She goes to hug him. "Daddy. Daddy." Her tone is not happy or comforted, but very distant and troubled. What kind of crap father-daughter relationship is this?

In the next few minutes all the misconceptions and misdirections will be straightened out, but the disconcerting sense that something is gravely amiss will remain. We find out this isn't a crap drama group but the SOMAFREE INSTITUTE OF PSYCHOPLASMICS, which sounds alarming enough.

Couple that with the disturbing though lowkey indications of a gravely troubled child and the fact that the child is found alone in such an institute, not to mention the discordant violins which never stop telling you that horror is on the way, and we find that the tension is building steadily.

The nagging nexus of parenthood, masculinity, dermatological affliction, and trauma, is somehow connected to a disturbed little girl. Remember the uncleanliness of leprosy and boils, and their link with childbirth from Leviticus? That's what's bubbling up, as yet just a suggestion. Though there'll be some pretty dry and dark comedy on the way as well.

At bathtime the absolute worst of the worst is revealed: bruises on little Candy's back show abuse. Daddy shoots back to the institute and demands to see his wife Nola. He's sure she did it. Did he get that from the child or is he just supposing? Dr Raglan asks. Candace won't talk about it. There's a standoff. Custody battles in court will ensue. They face off and the duel is on.

David Cronenberg had just experienced a painful divorce, and this horror film was envisioned as a kind of Kramer versus Kramer drama about the pain and conflict of an acrimonious split with children suffering the consequences. So much on his mind was the "battle of the sexes" as experienced through the process of divorce and custody proceedings. "The law believes in motherhood", says the movie's lawyer. Oh yeah? says Cronenberg. Well the law may believe in motherhood, but I think it stinks!

There are many ways you could go with the man-denied-custody-of-his-kids scenario. You could do it as straight drama of reasonable adults being all reasonable, as in Kramer versus Kramer. Which is so boring that this Oscar winner has been utterly forgotten. You could do it as a hilarious cross-dressing comedy like Mrs Doubtfire. Or you could go the way of The Brood and Possession and make it the subject for the most overwrought grotesque Gothic body-horror melodrama imaginable. That works too.

Being Cronenberg, the deep disturbing content goes hand-in-hand with the tongue-in-cheek comedy, which in this film is almost entirely at the expense of the ineffectual police inspector. The cops are Canadian cops, so where in an American crime thriller there would be macho posturing and tough-guy pantomime, here there's only polite ineptitude.

The detective explains why they never caught the killer - a child sized monster - when they searched the crime scene: "We searched the place but we weren't looking for anything that small, and we missed it." So you thoroughly searched the murder scene but weren't looking for anything as small as an 8-year-old child? Okay...

The policeman is working on the hypothesis that "some crazy woman didn't want anyone to know she had a deformed child. She's had this kid locked up in an attic for years and never told anybody. Wouldn't be the first time." Watch a lot of B-movies, Inspector? When they attend the autopsy, and the pathologist reveals that this is an entirely new species of humanoid never before seen by anyone anywhere. Protagonist Frank gets it, and is appropriately awed and amazed; the detective can't really understand anything that's happening.

So that's The Law: believes in motherhood, asks impertinent questions to a traumatized little girl and is dumb as rocks in a sack. The real authority is Dr Hal Raglan, Ollie Reed's bullying psychologist. He is the agency in the film, all actions are derived from him and all the other characters merely respond to his decisions. But finally even he doesn't have control or agency over what happens.

The prime mover, it turns out, is a mother's uncomprehending rage at her own childhood trauma. As Barbara Creed suggests: "Parthenogenesis is impossible, but if it could happen, the film seems to be arguing, woman could give birth only to deformed manifestations of herself." [Creed p45]

It is Samantha Eggar's Nola who is the animalistic source of the chaos and suffering, and she doesn't know what she's doing. She utters the anguished cry "Mummies don't hurt their own children!" but of course, says the film, they always hurt their own children.

While it is true that the film presents Nola as a victim of her upbringing, she is also mainly a victim of her mother and the latter is a victim of her own mother, and so on. Woman's destructive emotions, it seems, are inherited. [Creed p45]

And by the ending, little Candy... well, that would be telling.

—-INTERMISSION—-

I'm at war against women. They...have no foresight. There's nothing about them that is stable, there's nothing to trust. They're dangerous.

Mark in Possession

Unfortunately Barbara Creed never mentions Andrzej Żuławski's Possession, but there's so much to transfer from her commentary on The Brood to that film, so we're going to borrow a few insights from that text and splatter them like nasty stains all over the already-stained and bedraggled dress of Isabelle Adjani in the latter film.

It’s a film with nasty stains everywhere, making the phrase "a messy divorce" a literal portrayal of sweaty, grimy, dishevelled people and the slop of emotions dragged up from the taboo zones of anguish into the most sickening monster ever, one that's wildly erotic and carnal to the very suffering soul that gave birth to it.

Gazing into the eyes of Isabelle Adjani's eldritch child and lover, manifested out of despire and repugnance, one finds one has become blind, and has to thrash around wildly in a literal blind panic. Gazing into the eyes of Isabelle Adjani herself, one is taken into the depths of fear and confusion. Is this what I've become? the eyes demand. How did it come about that I caused so much pain, and that I suffer so much pain?

There are no easy answers to that, nor to the many enigmas that crop up in the course of the story: Who are the sisters Faith and Chance, and if Faith is a miscarried foetus oozing out into the subway floor, how can you protect it? What's Heinrich's deal, and more importantly what's Heinrich's mother's deal, and how do these neuroses connect? Why is the angelic Helen the double of the demonic Anna, and how come she is creepier? What's Mark's deal, and how did he get his suit so dirty? How can a woman armed only with a damp cloth overcome a man with an automatic pistol in close combat? Who is the man who only wears pink socks?

Seen through the lens of camp irony, this is an uproarious tramp through some of the wildest psychosexual weirdness ever, with some of the most outrageous lines to wonder at and repeat wild-eyed and giggling to your friends:

We are all the same. Different words, different bodies, different versions. Like insects! Meat!

I met a man who loved everything, and he died in a flood of shit.

You think you've given her the supreme pleasure? You with your yin-yang balls dangling from your zen brain?

You believe in God, don't you? That God you try to get to through fucking or dope.

If I lay at your feet and yelped like a dog would you still step over me?

That much it has in common with any good - or even bad - Ken Russell film.

Also like Ken Russell you find, as ever with Andrzej Żuławski, that what you lose in coherence and "good taste" you gain in thunderous raw power. Nothing will allow you to forget Isabelle Adjani's piece of primordial performance art in a subway tunnel, a legendary moment of film history.

After having gazed at a crucified Jesus with an intensity that seems like it would melt stone, she uses her groceries as a kind of kinetic art piece, a Jackson Pollock of smashed eggs and spilled milk, and then performs an interpretative dance of demonic possession. It's all topped off by one of the most grotesque emissions of protoplasmic slime, blood and ooze ever seen.

Look one way and it's an actress being goaded to the most over-the-top performance ever by a filmmaker who always relished hysteria; look another way, and here's a woman who is really being possessed by something unknown and rightfully taboo, and you want to look away but can't.

But beyond all the well-known body horror that has earned the film a place alongside Cronenberg's most splattersome work, there are elements that are just plain uncanny, in Freud's sense of being something familiar now made unfamiliar and vested with unearthly potential to disturb. One is the face of Helen, Anna's double and little Bob's teacher and eventual surrogate mother, and especially her green alien eyes.

Then there's Heinrich's little home movie which he made of his new lover Anna. Everyone likes to make videos of their partner, to keep a few images in motion of the one you love and desire. And what could be more cute and wholesome than her teaching ballet to a class of little ballerina girls? So when she begins to torture one girl and gaze directly into the camera with a confrontational look of defiance and cold rage, it's absolutely chilling. She says, addressing Heinrich and his camera:

From now on she'll know how much righteous anger and sheer will she's got in her to say, "I can do as well. I can be better. I'm the best." Only in this case can she become a success. Nobody took me there. That's why I'm with you. Because you say "I" for me.

That's strange and confusing - and taken at face value as the justification of the violent abuse of a little girl is simply psychotic - but it seems to point in some way to this critical issue of agency.

Heinrich, with his weird yogic martial arts and his handsy way with men and women, his monstrous ego and absurd New Age pseudophilosophy, gives her agency. Mark, with his fawning abject misery, his self-comparisons to a dead dog, his stuttering incoherence and failed rages - not so much.

She's prepared to do anything - torture children, give birth to eldritch miscarriages in a pool of gross groceries, even stab self-realization catalyst Heinrich himself - to preserve that sense of "I".

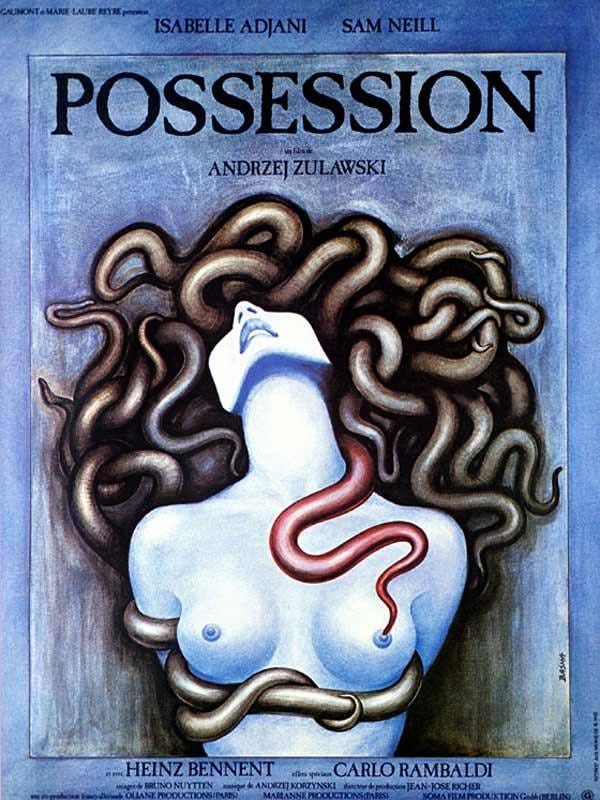

SIDENOTE ON POSTER ART

The poster by Barbara Baranowska is the greatest piece of cinematic poster art ever made, and although strictly speaking it's extraneous to the film itself, if you have it on your wall it complements the experience of having seen the film perfectly. What's unique about Polish cinema is how it seems culturally more complete than anywhere else, the poster art and the acting schools and all the superstructure there to service the production of high cinematic art.

It's not just the big moments of character that get the uncanny treatment. Even the routine business of plot mechanics is subject to disturbing/comic touches. So when Mark goes to the private detective's office, both he and the chief PI are in swivel chairs, and both will start nervously swinging to and fro, to and fro, out of synch. Their chat is inconsequential, and it's a good thing too, because it's impossible to concentrate with these absurd men oscillating out of phase like neurotic broken toys.

The film is fundamentally about war: war inside the psyche between competing desires to be good, caring and loving or selfish, spiteful and free; war between men and women as expressed in Mark's very frank words to Helen and his demeanour throughout; and the big one, the Cold War, which threatens to take all the civilizational discontents that derive from those massed fractured psyches and dramatize them, realize them, with nuclear exchanges that annihiliate them all. No possibility of a truce between any of these factions is proposed or considered, and the film is a nihilistic mess of universal and particularized war.

The War Zone 1) Personal

Like all of Żuławski's work it is a personal journey into pessimism and disillusion, made with conviction and an undisciplined raw skill that makes each part fascinating and maddening. It's unforgettable whether you choose to take it as a campy over-the-top melodrama with gross body horror, or a strained and stained allegory for the fear and awe around motherhood, the deep conflicts within us, and above all the death drive towards our own self-willed destruction.

Geez, Murph. I am falling woefully behind on my viewing as curated by yourself. I will have to carve out time to address this. Again, you write so well and your synthesis of disparate themes is impressive. Bravo again, friend.