Back to Back 4 - Of Things Transformed

Contrasting two stop-motion masterpieces soaked in imagination

The Wolf House (2018) writers, directors Joaquín Cociña and Cristóbal León.

Mad God (2022) writer, director Phil Tippett

Genre: Stop-Motion Fantasy Horror

Recommended snack: Putrifying foodstuffs like surströmming fish, limburger and gorgonzola cheeses, washed down with dark bitter spirits like Riga Black Balsam or Fernet Branca

Recommended listening: "Descent into the Inferno" Scraping Foetus Off the Wheel

Whether or not there really are manifestations of the supernatural, they are horrifying to us in concept, since we think ourselves to be living in a natural world... This is why we routinely equate the supernatural with horror. And a puppet possessed of life would exemplify just such a horror, because it would negate all conceptions of a natural physicalism and affirm a metaphysics of chaos and nightmare. It would still be a puppet, but it would be a puppet with a mind and a will, a human puppet — a paradox more disruptive of sanity than the undead... If they ever came to life, our world would be a paradox and a horror in which everything was uncertain, including whether or not we were just human puppets.

Thomas Ligotti The Conspiracy Against the Human Race (2010)

Ever since Luigi Galvani zapped a frog's leg with an electric shock, and Mary Shelley's Victor Frankenstein followed suit by creating a man and imbuing him with life from electric current, there has been the twin ontological problem posed by autonomata and puppets. Namely, what if we humans are merely squishy biological automata with no free will, no agency, but that we just imagine that we have it? Conversely, if we create a moving lifelike automaton, like a robot, does it have the same soul-stuff as we do?

Ernst Jentsch, one of the first psychologists to delve into "the uncanny", commented that of all "the psychical uncertainties that can become an original cause of the uncanny feeling, there is one in particular that is able to develop a fairly regular, powerful and very general effect: namely, doubt as to whether an apparently living being is animate and, conversely, doubt as to whether a lifeless object may not in fact be animate."

He went on to discuss horror literature in these terms: "Horror is a thrill that with care and specialist knowledge can be used well to increase emotional effects in general... In storytelling, one of the most reliable artistic devices for producing uncanny effects easily is to leave the reader in uncertainty as to whether he has a human person or rather an automaton before him." [1]

For Jentsch, then, the central unsettling truth in the uncanny has to do with this question of animation - is this thing before you a being with agency and will, or is it a lifeless thing that just flaps about? And what about you?

The puppet is a particularly problematic entity in this regard. And no practitioner of the puppet and its animated form is more uncanny than Czech filmmaker and artist Jan Švankmajer. A surrealist, he takes the very tactile principle of Habsburg court painter Guissepe Arcimboldo, the real-world materials of fruits, fish and plants, and transforms them into moving beings. The result is a puppet theatre of increasingly disturbing creatures, a truly uncanny space where the human, the inhuman, the living and the dead are mingled to produce beings that move like things in a nightmare.

In nova fert animus mutatas dicere formas corpora ("I will speak of forms changed into new entities")

Ovid, Metamorphoses

The Wolf House resembles and builds on the Švankmajer schema with a more radical technique. Švankmajer's Alice (1988) is close in spirit to The Wolf House, a deranged version of Alice in Wonderland which places a young girl in the midst of horrifying monsters and apparitions of all sorts. The Wolf House could almost be said to be a reimagining of Alice.

That film used stop-motion puppets made of animal skeletons and taxidermied cadavers. This film makes animations out of papier-maché, masking tape and untold quantities of oozing paint. Entities flow across the walls as living murals, dripping themselves everywhere as a tactile reminder of their physicality.

The Švankmajer puppets, though disturbing, were stable, remaining the same kind of thing from one moment to the next. In The Wolf House the animated entities are constantly changing, shifting from wall painting to primitive puppet, being made, unmade and remade as you watch. The effect is to create a space where nothing seems real despite the evident reality of the gritty physical textures.

The story relates to a cult of Germans who set up a compound in the far reaches of Chile in 1961 called Colonia Dignidad (the Dignity Colony). Directed by ultra-sinister cult leader Paul Schäfer, former Nazi and practising paedophile, the exiled Germans lived apart from the Chileans until the Pinochet coup of 1973, when the dictator decided to use the cult compound as a torture and execution centre. For a literal eyeblink we see the dark Nazi past of the sect reflected on the wall of the set, then it’s gone.

Departing from this dark real-world story, we experience the fairytale journey of a young girl, Maria, who escapes the abuse and goes to live in a hut in the woods with a pair of pigs. Soon she transforms them into weird pig-human hybrids and finally her "real" children, Ana and Pedro.

Now they are the three little pigs and outside their house is the Big Bad Wolf, the cult leader. He growls and coos at them in German; they speak a German-accented childish Spanish. But the film has been presented from the beginning as an official training film made by the cult leader, showing the impossibility of escape. So the conclusion is foregone.

Although it is only 73 minutes long, there is no telling how many hundreds of hours went into the making of this masterwork. Filmmakers Joaquín Cociña and Cristóbal León impressed Ari Aster sufficiently with this effort that he incorporated their work into Beau is Afraid (2023) in an animated sequence that was beautiful in itself but jarred badly with the overall direction of the film and brought Beau's quest narrative to a shuddering halt.

It's to be hoped that Aster, or some other ambitious director, will learn to better incorporate Cociña and León's work into theirs, or even better, that they get the funding to develop another film of their own. They could be just what's needed to shake up the routinely high-tech style of an animation series like Love Death and Robots on Netflix, which despite care to vary the visual style, has nevertheless settled into a kind of futuristic rut.

—-INTERMISSION—-

And if ye will not for all this hearken unto me, but walk contrary unto me; Then I will walk contrary unto you also in fury; and I, even I, will chastise you seven times for your sins. And ye shall eat the flesh of your sons, and the flesh of your daughters shall ye eat. And I will destroy your high places, and cut down your images, and cast your carcases upon the carcases of your idols, and my soul shall abhor you.

Leviticus 26: 28-31

Mad God begins with the extensive imprecations of the tribal war God Yahweh to the ancient Hebrews, showing that the old skydaddy is, of course, absolutely mad. That the Jewish-Christian belief complex includes this psychopathic drool in its holy scriptures should be enough to make us give any of its believers a wide berth, but instead of course we allow this death cult full access to our children - in spite of the fact that their god will make us eat said children if we step out of line. So who's more mad, the Mad God, or the mad humans who dreamt him up and then gave this imaginary maniac suzerainity over them? Look around you if you're unclear on that one, there are one or two hints present in world affairs that could point towards the answer to that conundrum.

Filmmaker Phil Tippett was a stop-motion master who created animation effects for the Star Wars original trilogy (1977-83) and RoboCop(1987). As stop-motion and miniature effects fell out of favour in mainstream Hollywood with the advent of CGI, Tippett began the Mad God project. Thity years later, with crowdfunding support, it was complete. What he made could never have been produced by the Hollywood studios, even though it cost what a blockbuster movie spends just on coffee. It is simply too much: too imaginative, too transgressive, too different.

Tippett sums up the aim of the project in words that reflect the aim of surrealist art of every time:

The final form of Mad God isn't the film itself, but the memory after you watch it. It's bringing you to that moment just after waking up from a dream, frozen, exploring fragments of your feral mind before they fade back into the shadows.

This it does by injecting a dense solution of symbols and references, many drawn from surrealist and expressionist art like the work of Otto Dix and Max Ernst, into a fragmentary yet archetypal narrative. From Lynch it takes a fearless determination to get into the most uncomfortable spaces of our "feral mind" and explode them, free them for the sort of scrutiny and consideration that promotes understanding of what we are.

Above all, Mad God grapples with the elemental Problem of Evil. It doesn't attempt to answer such a headscratcher itself, that would be hubris enough in an 80 minute animated film, but it does attempt to dig around in it, exposing some nasty pustulent material on the way. Clearly there is a link between cruelty, in both its sadistic and indifferent forms, and the existential threat of war and species annihilation which follows from it. There is a vast cold machine which consumes the beings it creates and which create it. But the film is an experience, and though it may be allegorical, it does not reduce to the banality of a political polemic. Whether it is good art or bad art, it is a work of art, and deserves to be considered as such.

As the film progresses, if that's the right word, the story will scream to a halt, loop back on itself, stagger towards a conclusion, fail to conclude, then transmute into the cosmic ritual creation of the entire universe. By this time you have either lost interest entirely or been absorbed by the staggering imaginativeness at work here, bullied as it were by the power of the imagery.

Along the way you have been introduced to demented versions of Lynch's Eraserhead (1977) and Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), as well as video games like Fallout, Bloodborne and Silent Hill. Like the ingredients in some mad alchemical potion, these are churned up into a tasty broth of elemental evil and nightmarish discomfort, to create an experience that is unforgettable and unrepeatable.

The protagonist, a being straight out of Fallout by way of Otto Dix Great War paintings, with retro-military gear, a gasmask and a morally ambivalent attitude, sets out in a capsule to plumb the depths. The capsule goes deep, past the superficial layers of the underworld where flak guns blast at it, through layers where forgotten gods crumble into dust, and into the deepest layers of primeval existence.

Here there are abominations and depravities, things with slimy teats and nightmarish faces that delight in chopping up deformed victims, but even here is not deep enough. So the protagonist goes deeper, where cruelty exists for its own sake. There we see machines of vile imagining, torments so baroque there is no word for what is happening, only words that hint at it - surgical, coprophagic, electroshock. But this is still not deep enough.

So we descend further, into the territory of Lovecraft's eldritch beings of pure madness "a shapeless congeries of protoplasmic bubbles, faintly self-luminous, and with myriads of temporary eyes forming and unforming as pustules of greenish light." Beyond and beneath this Shoggoth-sphere is what seems the final depth, a machine which takes all the distilled cruelty, madness and suffering from the upper circles and forms beings from it to work enslaved for its ends.

This industrial hell is the true inferno, a vision of a system which functions only to keep itself functioning, in which anonymous beings are ground up and consumed as they toil to produce more machinery for their own immolation. Here the cruelty is not joyfully sadistic, but impersonal and indifferent, merely the system working as designed. It is the vision of the industrial Moloch from Metropolis (1927), or the machine dystopia of Matrix (1999), made more gruesomely detailed than ever before. Naturally there are hints too of the industrial process of death that was the Holocaust.

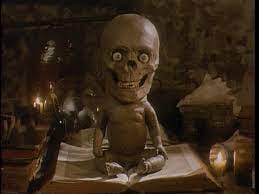

During the descent there was a musical score, a descending discordant piano playing subtly in the background and reinforcing our sense of continuing exploration of the depths, but here in the Moloch-hell there is only a soft lullaby mixed with the babbling of a baby. This infantile jabbering is revealed to be the voice of the devil that presides over this deepest circle of hell, another eldritch creature made of TV screens and diseased flesh. It summons the tormented creatures to listen to its endless babble, and they listen while waiting to be consumed by its machinery.

But the protagonist must venture deeper still. Down steps that evoke horror cellars and into a realm of pure subterranean terror like The Descent (2005), to a place where abandoned suitcases are piled high, a place we've been to in our documented historical shared nightmare. Here the protagonist reveals the contents of his own suitcase, a timebomb. Is his plan to assassinate the Mad God that presides over all this suffering? But the timebomb will soon stall out as time apparently runs towards stasis. And before the audacity of this plan has time to settle in, our man is captured by a demon and sent for enhanced interrogation.

Like real-life enhanced interrogation, as practised in black sites the world over, the purpose is not the extraction of information but rather theatre, a performative display of dominance and abject helplessness. Being secret, we are not invited to witness the event, but since we know it happens we are left to reconstruct our own version of the entertainment. So, logically, in this allegorical hellworld, the torture is actually a stage production, performed as shadow theatre with an appreciative audience.

Now our man is left alone, bound tightly and bandaged, only a single horrendous bloodshot eye - our mind's eye - left to witness what happens next. The cinematography now jerks into full nightmare mode, crackly aged filmstock, janky editing and shutterspeed, to take our mind's eye directly into the dreamscape of helpless terror. In come the surgeons, puppet-like and uncanny in their inhuman motion.

They slice him open and rummage around deeply in his guts and ooze. Icky shit splatters everywhere. More rummaging, gold and jewellery extracted and discarded. Bloody slime oozes down the walls. But there it is, the treasure: a misshapen monster, a creature birthed from deep inside, crying like a newborn. We are deep in Eraserhead (1977) territory now. But meanwhile the torment goes on for the protagonist: the surgeon drills a sizeable hole in his skull and a camera probe is inserted. With this intrusive camera, which no doubt means death for the protagonist, we pass through TV static to access the memories of the surface world.

The surface of the world revealed through these memories is a lot more like ours, as the militaristic orchestration of violence appears to have some kind of purpose. The level of horror here is Otto Dix Great War rather than full Lovecraftian eldritch, and thus a kind of comfort compared to what has come before. Moreover it is a live action sequence rather than stop-motion, which gives it yet another reassuring dimension. Strange to suggest that a world of Great War horror and squawking unidentified creatures is cosy and homely, but so it is in the context of what has preceded it.

This world and its Dix-stormtrooper legion is presided over by a character known as The Last Man, played by cult director Alex Cox, a grotesque-looking personality even without the claw-like talons on his hands and feet. His enslaved monster creatures have stitched together a map to the labyrinth at the centre of hell, which he gives to another protagonist as he send the capsule on its way. The narrative loops round once and starts again.

The previous agent - assassin, envoy, spy or whatever - had a bomb in a suitcase and a paper map that disintegrated at the touch. This one has a suitcase and a map scrawled on hide - or is it human skin? The new guy jacks a motorbike and begins his ride to the centre of hell. He processes through a post-apocalyptic cityscape and the Fallout vibes intensify to fever pitch. Eldritch monsters return: phage viruses as tall as skycrapers, and Max Ernst bird-succubi jerking off minotaurs in sidestreets.

When the second assassin's motorbike gives out, he takes an old kubelwagen and moves out from the ruined cityscape into a devastated warzone. Here the filmmaking is based on painstaking miniature work, the kind of thing that simply isn't done any more. It is fascinating to see the models brought to life, the unreality of this very real physical medium, and how like stop-motion puppetry it breaches the uncanny in being both lifelike and unlifelike.

The noise of distant geese takes us into a nuclear war - an allusion to the 1950s incident in which a flock of geese set off early warning systems and triggered a nuclear alert. As the nukes rain down above, our guy drives his vehicle into the abyss below, down an impossible spiralling ramp.

We return through the television static to the surgeon and the eviscerated husk of our original protagonist. The nurse is taking the monstrous baby which was torn from the innards of the protagonist to be offered up to a... a thing. This thing is perhaps the most terrifying of all the many monsters and demons Tippett has presented us, largely unseen beneath a veil of shamanic talismans and gently crooning Italian, the only coherent human speech in the film.

Later it will be seen to be a medieval plague doctor, with huge beak and googling gas-mask eyes. Yet the hands alone, the way they deploy, is as uncanny as anything ever seen.

The monster-baby is taken through chambers of enormous statuary, eerie and ancient, including one of those pig chef figures you see outside tacky restaurants. The creature passes through a drawbridge gate guarded by a pair of minotaurs.

And now we are in a Bloodborne world: the gothic ruins, the eldritch statues with parts from seacreatures, laboratories with unknown specimens in jars, the eerie shamanic figure, a plague doctor gliding like a ghost with wafting tendrils of dark ribbon rags. In this world gigantic mindless creatures clobber each other until a warty man comes to shock them into submission. Then they settle down and get to work shovelling shit into enormous mounds, a sisyphean task as more shit is always being droppped into them. Frustrated, they jab at each other and the cycle starts again.

The Warty Man is charged with the care of a domain of beautiful bejewelled fungi which he keeps sustained by dropping worms into it. This wondrous world is gorgeous, richly coloured and inhabited by a pair of psychedelic fungus creatures who relish the wormy snack he left for them. So naturally the warty man releases a brightly coloured predator monster to gobble them up. He very much enjoys that. The Plague Doctor arrives, and it is clear that the Warty Man is Igor to the Plague Doctor's Frankenstein. A transformation of some kind is to take place here. Sure enough, the monstrous baby born from the eviscerated guts of the first assassin is prepared for whatever unspeakable rite is to happen here.

The baby is ground to goo, its slimy substance put through an obscure alchemical process and the resulting sparkling magic powder cast by the Plague Doctor into a furnace. The resulting alchemical transformation is cosmic in scale, another hallucinatory trip through the symbolism of transformation to rival Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) or Panos Cosmatos' Beyond the Black Rainbow (2010). As pulsing urgent music throbs, whole planetary systems are created, biospheres grow and flourish and finally a city rises. Anarchist rebels plant bombs, the city is destroyed. Death overcomes teeming existence, a black hole reigns where a planet full of life once stood. The black hole emits monoliths which go spinning through space.

Time stands still; time leaps ahead; time reverses. The scenes and images from the film spin wildly out of control. Entropy rules and decay holds sway. The clock on the timebomb restarts and hits detonation. A grotesque red bird emerges from a cuckoo clock and cuckoos wildly. Cut to black.

[1] Ernst Jentsch, "On the Psychology of the Uncanny"