Back to Back 59 - Take Shelter in Your Sadness

2011 dramas that take the personal apocalypse of dread and make it universal

Take Shelter (2011) - writer/director Jeff Nichols

Melancholia (2011) - writer/director Lars von Trier

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

This is the way the world ends

Not with a bang but a whimper

T.S Eliot, “The Hollow Men”In 2011, the hot new thing was the prescient awareness that a huge celestial body would come crashing into the Earth in December 2012 and end all human life, blasting the planet to smithereens. When that event duly occurred in December 2012, we dusted ourselves off, put the drifting fragments of our homeworld back together, and got on with the rest of our post-annihilation lives.

Nothing would ever be the same again: that particular entertainment trend was over forever, at least until some other pseudoprophetic crap could come along and revive it. This now-defunct 2012 scare had been sparked by something about Maya calendars - and there are lots of other calendars, with lots of other end dates, out there to be exploited in our thirst to distract ourselves from the authentic dateless apocalypse creeping in all around us.

Meanwhile something had to fill the yawning gap in our blockbuster world. That something was superhero sagas all connecting together to form a beast called a "Universe" and later a tentacular entity called a "Multiverse". And so began the slow descent into superposition: the universe where interest in superheroes grew forever disconnecting (in technical quantum jargon 'decohering') from the timeline we live in, where nobody gives a shit anymore about men and women in tight-fitting bodysuits with laserbeams in their eyes.

But let's blast back to that other world of 2011 for a moment. Though Obama had promised hope and change, what we actually got was despair and stasis. Amid the boring dystopia that was post-2008-crisis late-capitalism, a crashing down of celestial apocalypse (though high perhaps in end-time anxiety) at least promised some relief to the hideous tedium that we have all experienced ever since: that squeezing of financial possibility, and the widening vista of grinding, ever-more-desperate, fending-off of poverty. The sweet release of universal death seemed blessed by comparison, and 2011 cinema had seemingly no end of apocalypse to offer.

Here is a frightening thriller based not on special effects gimmicks but on a dread that seems quietly spreading in the land: that the good days are ending, and climate changes or other sinister forces will sweep away our safety.

Roger Ebert review of Take Shelter "A dread is spreading in the land"

It stars Michael Shannon! That just about settles it as a must-watch, whatever else may be going on. In fact quite a bit else is going on other than the huge Shannon performance that anchors the piece. There's Jessica Chastain as his wife, for one, a solid performance in a rather thin and thankless role. There's the creeping buildup of dread as Shannon's character Curtis experiences nightmares and visions that may be prophesies of apocalypse, or else growing delusions in a developing episode of schizophrenia.

The horror is subtle and powerful, conveyed more by Shannon's unease and sense that something unexpected may leap out of his unpredictable reactions at any moment. We might compare his performance in this film with that in William Friedkin's Bug (2006) or in Werner Herzog's My Son, My Son, What Have Ye Done? (2009). In the first, he was manic and grotesque, a grand guignol of edgy and theatrical paranoia; in the second, sinister in his contained rage and clearly dangerous.

Here, he's clearly attempting to hold himself together under enormous strain, and do it all alone. The solid working-class Curtis has built a persona for himself out of American archetypes of stoic endurance and cannot talk about his increasing vulnerability to the person closest to him - but will attend a free clinic to talk to a psychological counselor. Above all, he seeks to construct the perfect shelter to ride out the storm.

"I think it''s a very poetic expression of a question which I've been struggling with for almost my whole life, which is 'How can you live in the world in which we live and not lose your mind?'.... Everyone has a storm that's coming. Everyone has something on the horizon that doesn't seem like good news."

Michael Shannon interview on Take Shelter

That ‘something’ may be hereditary madness, a biblical apocalypse, a climate crisis unleashed with a touch of Hitchcockian malice from a vengeful planet - which all of us suffer to a greater or lesser extent - or the creeping fear of slipping out of the decent working-class and into abject poverty, with no income, no respect and no healthcare whatsoever.

For this is an American story, and so the truest horror on show isn't Curtis's nightmarish visions, but the prospect that the cure for a little girl's condition (in this case deafness) depends entirely on her fragmenting father's precarious hold on his employment and his health insurance plan.

For this reason the carefully-cultivated ambiguity of Curtis's visions, true prophetic gift or schizophrenic delusion, is not necessary to resolve into one unambiguous explanation by the end of the story. It's a mark of the story's maturity that this is the case, for to pronounce one way or the other would be to close off the creeping dread that the film has built up, and has resonances in our real world.

A close analogy is the 1996 psychological horror Jacob's Ladder, realised with a great deal more histrionic fervour by Tim Robbins than this relatively restrained performance by Shannon. In that film the ending threw out a lot more doubts than were generated in the course of the narrative, and to powerful effect. Such is the case in Nichols' film.

If this were a European indie drama, an Antonioni or a Haneke joint, nobody would blink at the unresolved nature of the ambivalence. But it's only because expectations are high that in a meat-n-potatoes family drama of life in the mid-West the story must resolve in one way or another that the film failed to score many converts.

SonyCorp, after seeing that Nichols won the critics' prize in Cannes in 2011, bought the exclusive rights to the film for an undisclosed amount. Then, not having any idea what to do with this work, not clearly a horror movie, nor for that matter a not-horror, and having no feeling at all for the writing or performances it embodies, simply dumped it: it got a limited release and was forgotten in the swell of more obviously-generic and big-budget disaster fantasies in that Great Year of Disaster 2011-2012, the year we all met our end in a Mayan Apocalypse.

— INTERMISSION —

The only redeeming factor about it, you might say, is that the world ends

An awkward return to a troubled family - not just a common enough motif for Lars von Trier, present in many of his films, but a classic of novels and films since such stories, stories based on the bourgeois family and its discontents, became a staple of popular entertainment. Leo Tolstoy said that happy families are all the same, while unhappy families vary deliciously, and von Trier has surely taken that on board. You might think of Paul Newman's Brick and Elizabeth Taylor's Maggie in the appallingly shrill melodrama Cat on a Hot Tin Roof (1958), which in many ways could serve as a template for the dramatic story in the first part.

We start (following the overture which treats us to some bravura filmmaking and a taste of Wagnerian magnificence) with a stretched limo that's having trouble negotiating the tight curves of a winding country lane. This is a perfect metaphor, not just for the growing anxiety of Justine the bride, but for Lars von Trier's journey in the large vehicle of a polished mainstream drama film.

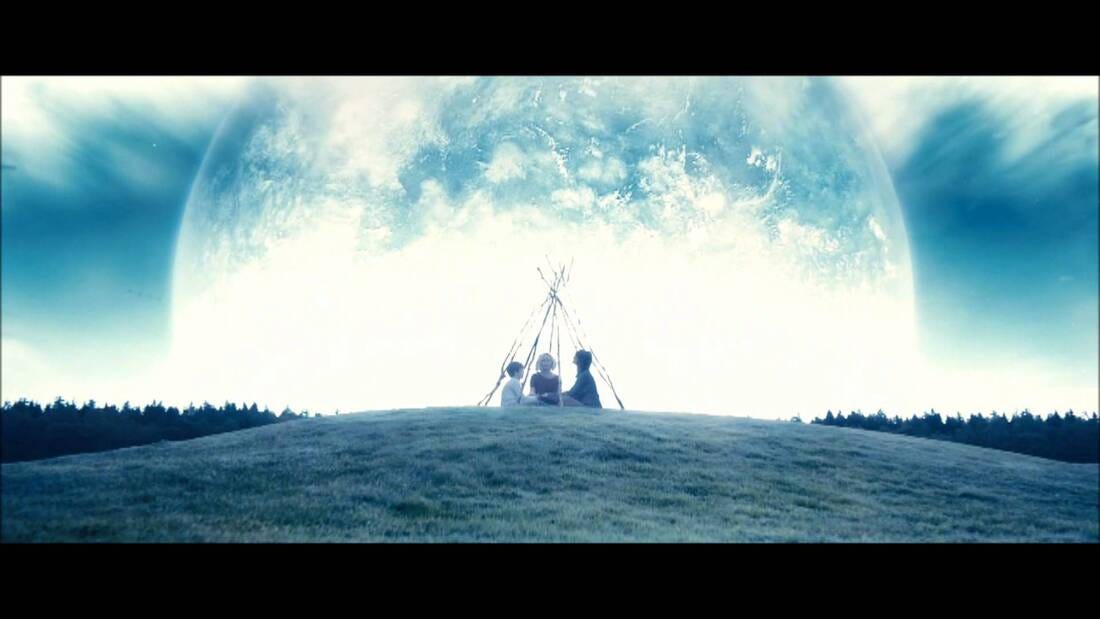

It’s a rare excursion for the punkish and often forbidding Lars von Trier into fine artistic montages to the luxuriant music of Wagner, taking a photogenic journey through the thickets of the titular melancholia - that is, deep and intractable depression. Antichrist (2009) prefigures this (and is considered a companion in a notional trilogy along with Nymphomaniac from 2013), but the previous film was framed in genre horror, and this film takes domestic melodrama and frames it in universal sublime dread. It's a relatively commonplace saying that to suffer depression is like being hit by a large object, to be stunned, and from that to a planet impacting our Earth and annihilating it completely is a short journey. It’s why Justine doesn’t feel much different as the apocalypse beckons.

Like Werner Herzog before him, von Trier is both attracted to the sumptuous beauty of German High Romanticism - the sweeping tones of Wagnerian opera, the perfect panoramic compositions of nature as executed by Caspar David Friedrich - and wary of their seductive power to usher the subject into a state of beatific bliss in which any amount of horror or atrocity can become tolerable and tolerated. He flirts dangerously with both artistic indulgence and a fascination with German-ness here.

On the sheer indulgence of the image and music, he has said:

For years, there has been this sort of unofficial film dogma not to cut to the music. Don't cut on the beat. It's considered crass and vulgar. But that's just what we do in Melancholia. When the horns come in and out in Wagner's overture, we cut right on the beat. It's kind of like a music video that way. It's supposed to be vulgar. That was our declared intention. It's one of the most pleasurable things I've done in a long time. [Interview, 2011]

The slow-motion montages, the exotic imagery of horses in lush forests and vast planets in the sky - it's all seriously 'vulgar' in the manner of 70s-album-cover-art, and in its totality becomes the polar opposite of the approach in his austere and deliberately-ugly Dogme 95-influenced films, and the severe staging of Dogville (2003) and Manderlay (2005). And of course all this visual and auditory lushness is equally pleasurable for the director and for the audience who are bathed in the sublime melancholy of the second part after an excruciatingly awkward night at the wedding banquet.

On the German-ness and its seductive beauty and terror, von Trier goes on to say:

When my mother was on her deathbed, I found out that I wasn't a Trier after all but came from a German family. I always found Nietzsche interesting and now I'm reading Thomas Mann. The Germans have always influenced me... I have always flirted a bit with the good Herr Wagner, and in Antichrist we inched towards a kind of German Romantic painting. Indeed, sturm und drang and everything that followed... the Nazis certainly cut on the beat. They didn't pussyfoot around. I've always had a weakness for the Nazi aesthetic... A lot of Nazi design was amazing. They had such big thoughts.

This flirtation with the Nazi aesthetic, exploring the atrocity in his own background and taking the fascination with Wagner and German High Romanticism to a forbidden extreme, would of course lead to von Trier's disastrous outburst in Cannes while promoting Melancholia in 2011. In that moment, seated with a mortified cast, von Trier half-jokingly started to explore his own Nazi dark side, concluding that "I am a Nazi," a remark that would have him banned from Cannes for a year.

Everything of course rides on the Melancholia of the title. It is both the disaster awaiting us and our sad planet, and the particular melancholy of the depressive Justine (Kirstin Dunst). The double meaning is both very apparent and pervasive throughout the film:

Melancholia is the name of the planet that, as a carrier of destruction, subjects the film’s characters to an existential problem. At the same time, melancholy is part of the personality of the main character, Justine. In a similar fashion, owing to its saturnine nature, in the history of melancholy, the macrocosm and the microcosm, the planetary and the personal, become one.1

This to the extent that the personification of nature (known as 'pathetic fallacy', where landscape mirrors mood) is firmly in place, as Heikkila notes: "Melancholy was the humor of Earth and Saturn and of the season of autumn... Notably, the film’s setting is autumnal throughout its events, tying psychology and landscape together."

The plot, as far as the plot goes in any way beyond that simple parallel of Melancholy-the-world-ending-disaster and Melancholy-the-annihilating-condition, also takes in an anecdote that von Trier heard from a therapist whereby depressive people react calmly to impending catastrophe while 'normal' people tend to panic. So Justine's sister Claire (Charlotte Gainsbourg), well-adjusted, happily married and solidly wealthy, with a son and contented family life, goes to pieces as the scale of the disaster becomes clear, while Justine takes it in her stride.

There's a radically disjointed two-part structure to the film, with the first part, the wedding banquet, being an unpleasant dive into Justine's world up to this point, her stressful Mad Men-like career in advertising with the overbearing Stellan Skarsgård as her boss, her drunken and abusive father Dexter (John Hurt), and the prospect of understanding and happiness with the mild-mannered Michael (Alexander Skarsgård).

But of course her chaotic slide into depression and nihilistic rage on her wedding night puts and end to this phantasm. This is the part resembling the melodrama of Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. It's messy and awkward, and with Kirsten Dunst's powerful performance effectively sets the stage for the 'disaster movie' to come. Her depression is large as a planet, and it's threatening to destroy her world. In fact it already has. It’s now for the world to catch up with her.

In the second part, with a change of approach from the chaotic family melodrama, we have the movement to the High Romanticism in which melancholy is a thing of sublime beauty in addition to being a crippling psychic condition. It's entirely appropriate that the aesthetic changes from the hand-held style of documentary-style realism to what von Trier himself describes as an atmosphere reminiscent of Luchino Visconti's operatic dramas.

Of course this has been foreshadowed by the prologue sequence, but the long section in the wedding night has obscured it again. Now it will return to be the only style available for this de luxe journey into universal annihilation. Where Antichrist ventured into Gothic fantasy and folk-horror imagery for its nihilistic explorations, Melancholia will take the Wagnerian high road into the end-time.

The result is a film that is extremely non-Trier in its approach, grandiose and - if not for the obliterating pessimism, perhaps - eminently accessible to the mainstream audience. It could well be that this sense of alienation from the final product ("I don't know this film") is what pushed von Trier over the edge in the publicity tour for the project, making him lash out and effectively destroy any good word-of-mouth that the film might have generated at its release at Cannes. Certainly, in the moments immediately prior to the Cannes debacle, von Trier sounds less than wholly enchanted with what he has made:

It consists of a lot of over-the-top clichés and an aesthetic that I would distance myself from under any other circumstances... I'm usually madly in love with everything I do. I'm probably the most self-satisfied director you'll ever meet. But this film is perilously close to the aesthetic of American mainstream films. The only redeeming factor about it, you might say, is that the world ends.

Von Trier in interview, 2011

Martta Heikkilä, "The End of the World in Lars von Trier's Melancholia”, in Lindberg & Schuback (eds) The End of the World: Contemporary Philosophy and Art (2017)

This reminded me to watch Jacob's Ladder again. What a phenomenal movie.