Back to Back 64 - Everything Everywhere All Over Again (Part 1)

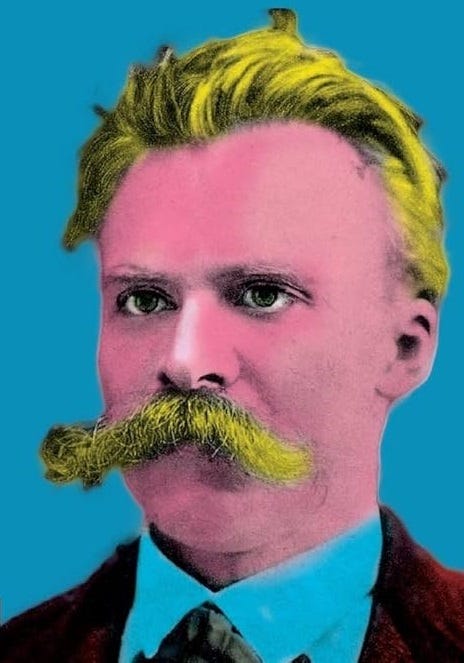

Sci-fi epics departing from the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, bushy-mustachioed incel and horse-lover extraordinaire

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) - director, co-writer Stanley Kubrick, co-writer Arthur C. Clarke

Arrival (2016) - director Denis Villeneuve, writer Eric Heisserer

A Frivolous and Unserious Beginning

The madman jumped into their midst and pierced them with his eyes. 'Where is God?' he cried; 'I'll tell you! We have killed him - you and I! We are all his murderers... What were we doing when we unchained this earth from its sun? Where is it moving to now? Where are we moving to? Away from all suns? Are we not continually falling? And backwards, sidewards, forwards, in all directions? Is there still an up and a down? Aren't we straying as though through an infinite nothing? Isn't empty space breathing at us? Hasn't it got colder? Isn't night and more night coming again and again?

Nietzsche, The Gay Science, Book III, Section 125 "The Madman"

Nietzsche declared God dead in 1882, though there are many theists who protest that, to paraphrase Mark Twain, reports of his death have been greatly exaggerated. Nietzsche had a comeback ready for that too (as he had a comeback for everything): "God is dead; but given the way people are, there may still for millennia be caves in which they show his shadow. And we must still defeat his shadow as well!"

Nietzsche was many things which are not exactly acceptable to many people: militant atheist, eugenicist, reactionary, moustache-wearer, virgin. He preached primal strength and warrior fortitude but had been medically retired from military service. He preached liberation and freedom - but only for the "best sort"; meanwhile the common herd "the descending line" should just shut up and realize that they would be happier to be uncomplaining in their naturally inferior place.

Though to be fair to this prototype California techlord and incel supreme, he considered himself only half-superior and half of the inferior sort. This was his great advantage, he believed; being slap-bang in the middle between the ascending and descending line of humanity, he could observe best the difference between the 'master' and 'slave' lines of human.

It's a familiar line today, and indeed Nietzsche well deserves to be considered The First Incel, the Ur-Alpha (or Sigma or whatever). Then why take note of this awkward customer? Two reasons: first, while his answers can sometimes be ridiculously wrong, his questions are always remarkably and primordially interesting; and second, his prose really can be some of the most magnificent in the Geman High Romantic style ever written. He is the master polemicist and declaimer of his time- none better, except perhaps Marx.

His legacy is eternally disputed between traditional conservatives (atheists: love; believers: love, but work very hard to ignore the elemental atheism and pretend it's incidental); liberals (thanks to Walter Kaufmann's doctored texts of the 1950s, Nietzsche was presented as a mid-20th century existentialist of the Camus sort and therefore acceptable to secular liberals); and socialists (following Bataille, and later Foucault, Deleuze and Guattari, there's been a concerted attempt to make Nietzsche’s thought amenable to the left; classical Marxists still think he stinks, but find his concept of ressentiment useful to keep them away from negativism).

Two of his central doctrines - taken variously by readers as thought experiments, symbolic representations, or as literal prophecies and precepts, are going to be central here. For Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, the key text is Thus Spoke Zarathustra, with its prophecy/programme for the "Übermensch", the next stage in human development. Kubrick inserted this text as a mythical substrate, believing as he did that the story can operate as a subconscious text underlying the surface story. As he reached his "mature style" with this film, it became a central part of his artistic practice from this moment on to insert one or more subtextual mythic layers.

Meanwhile, and much more explicitly, Denis Villeneuve's sci-fi drama Arrival makes use of the circular time concept of Nietzsche's Doctrine of Eternal Recurrence (again, treated as a thought experiment in validation of one's present life by most readers, though intended by Nietzsche as a literal metaphysical belief). There are parallel concepts of circular time in Eastern philosophy as well, and these are similarly present in Arrival. But it's Nietzsche's description of repeating circular time that is most relevant to this film.

There was once a star on which some clever animals invented knowledge.

It was the most arrogant and most untruthful minute of world history, but still only a minute...

Nietzsche, "On the Pathos of Truth" (1872)

The idea that Kubrick was deliberately infusing his sci-fi epic with Nietzschean themes is acknowledged but rather lazily dismissed by a leading "Kubrick scholar", Michel Chion, in a monograph on 2001, published in 2001:

With his symphonic poem Also sprach Zarathustra (Thus Spake Zarathustra, composed in 1896), Richard Strauss tried to translate into music some of the themes expressed in Nietzsche’s text... However, the triumphant effect of this music in the film seems to me no more tied to Strauss’s title and the content of Nietzsche’s work than the title of the ‘Blue Danube’ is tied to the idea of a central-European river and the colour blue. A musical piece that is ‘borrowed’ and integrated into a film is not some sort of enigma whose key can be found once you identify its title, its composer or any programmatic associations it carries. If Kubrick had chosen a different part of the same symphonic poem by Strauss, which is a collection of very diverse musical moods in terms of style and tempo, it seems obvious that the meaning of the sequence would radically change.

Michel Chion, Kubrick's Cinema Odyssey (2001)

But Kubrick didn't choose a different part of Strauss's music, he chose that particular part, which expresses grandeur and awe - expressive of the huge themes and scope of the film's visual style and story - much more than the ‘triumph’ Chion suggests. 1

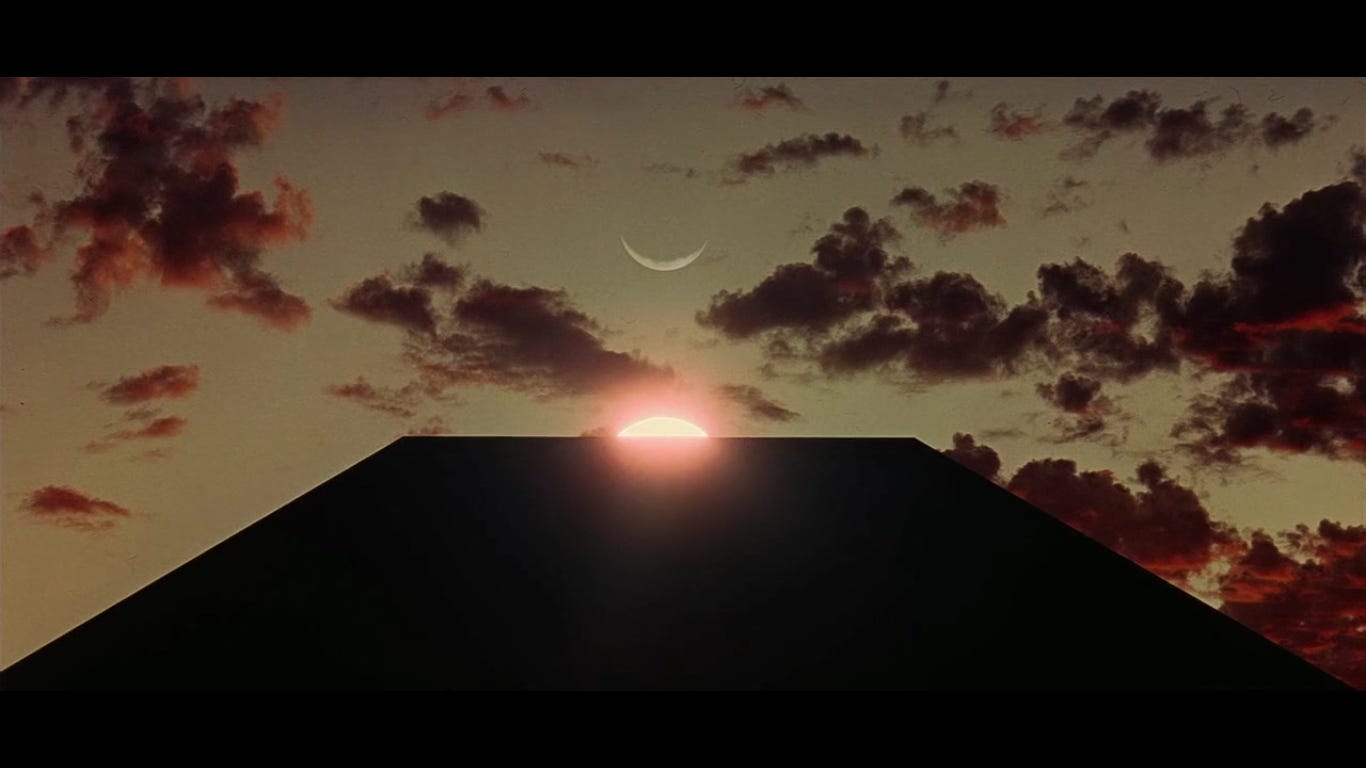

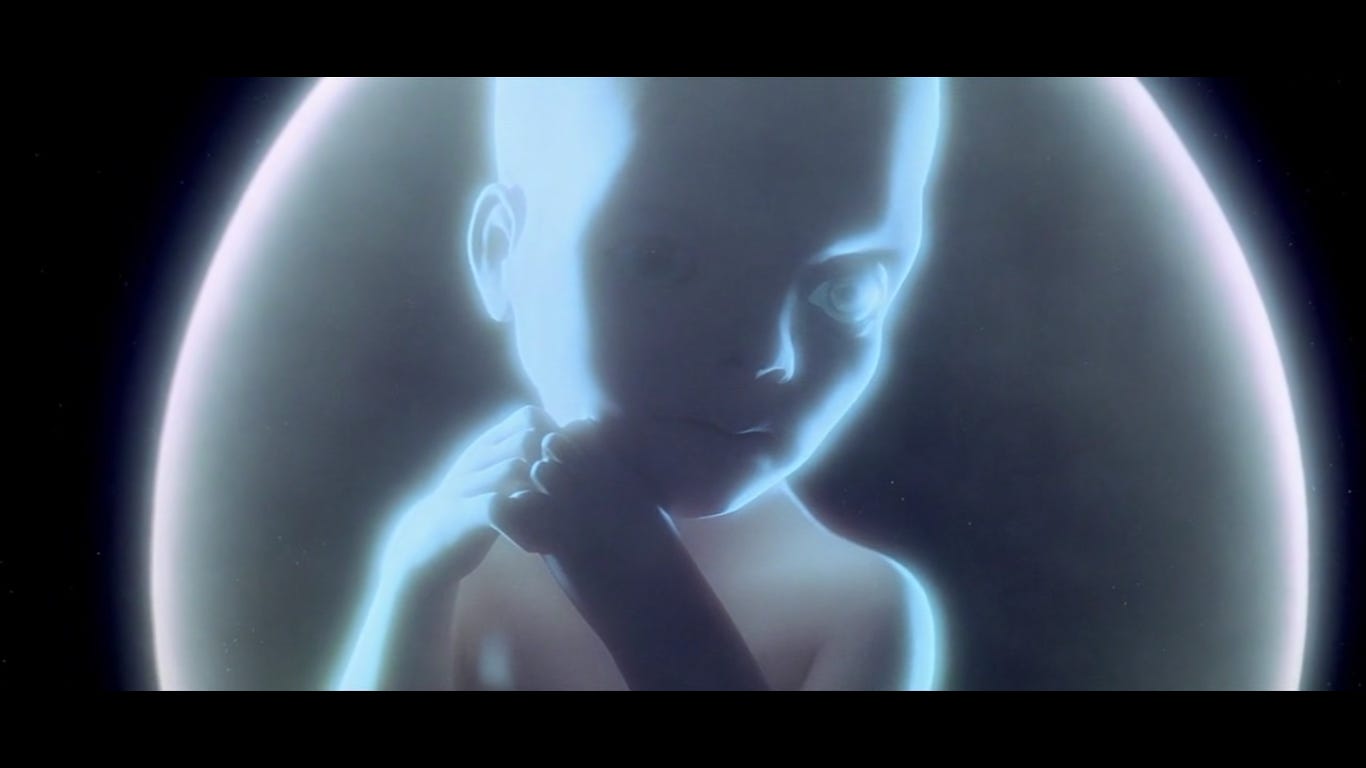

The music - repeated at the critical moment when the hominids encounter the monolith, and at the end with the revelation of the "Starchild" or evolved human created from Bowman - clearly links the film's score with the theme of evolution into distinct stages, symbolised by the monolith and its transformative power. That’s to say, it's Nietzsche through and through.

For Chion "it seems" that the music and its explicit link with Nietzsche's work has no more significance than the 'Blue Danube' waltz connects with the colour blue. But did he think to check the Nietzsche text... just to make sure? Or would that seem a bit too much like hard work for a guy who watches videos for a living?

Because for anyone who bothers to actually look at that text, and its predominant theme of the future evolution of mankind toward an "Übermensch" (variously translated as "superman", "overman", "overhuman" or possibly best of all from our 21st-century perspective "trans-human", even "post-human"), the connection is evidently there in Kubrick and Clarke's 2001 story.

Anyone who actually knows the Nietzsche text and watches the film with the musical cue in mind will see it: the progression from ape to "higher man", the death of God (a false idol of course, a supposedly infallible entity that lies to its followers and dies when they see the truth), the progression on a precarious tightrope between past and future, the birth of a new being in the dawn.

What's Kubrick doing? The new working method he developed for 2001 was strongly influenced by continental film theory and practice - perhaps most of all by Antonioni and Bergman - and a close study of the very visual language of avant-garde experimental shorts.

Though he has the reputation of not wishing to explain his films ("'Explaining' them contributes nothing but a superficial 'cultural' value which has no value except for critics and teachers who have to earn a living"), he had no hesitation at all in describing his creative method and its aims:

The problem with movies is that since the talkies the film industry has historically been conservative and word-oriented. The three-act play has been the model. It’s time to abandon the conventional view of the movie as an extension of the three-act play.

[This and subsequent quotes: Kubrick interviewed in Joseph Gelmis, The Film Director as Superstar (1970) p302–304]

2001... is basically a visual, nonverbal experience. It avoids intellectual verbalization and reaches the viewer’s subconscious in a way that is essentially poetic and philosophic. The film thus becomes a subjective experience which hits the viewer at an inner level of consciousness, just as music does, or painting. Actually, film operates on a level much closer to music and to painting than to the printed word, and, of course, movies present the opportunity to convey complex concepts and abstractions without the traditional reliance on words. I think that 2001, like music, succeeds in short-circuiting the rigid surface cultural blocks that shackle our consciousness to narrowly limited areas of experience and is able to cut directly through to areas of emotional comprehension. In two hours and forty minutes of film there are only forty minutes of dialogue.

So point one: it's not a play, a novel or a treatise. It's a visual artwork which is related to poetry, music and of course visual arts like painting. Point two: as filmmaker, Kubrick isn't trying to reach the conscious mind, but the unconscious mind:

I think one of the areas where 2001 succeeds is in stimulating thoughts about man’s destiny and role in the universe in the minds of people who in the normal course of their lives would never have considered such matters. Here again, you’ve got the resemblance to music; an Alabama truck driver, whose views in every other respect would be extremely narrow, is able to listen to a Beatles record on the same level of appreciation and perception as a young Cambridge intellectual, because their emotions and subconscious are far more similar than their intellects. The common bond is their subconscious emotional reaction; and I think that a film which can communicate on this level can have a more profound spectrum of impact than any form of traditional verbal communication.

What's doing this work of communicating to the subconscious (or unconscious or preconscious) mind? Images, of course, music, and an underlying layer of myth. After describing the "surface layer" of the film, the aliens and monoliths and the computer HAL, Kubrick goes on:

Since an encounter with an advanced interstellar intelligence would be incomprehensible within our present earthbound frames of reference, reactions to it will have elements of philosophy and metaphysics that have nothing to do with the bare plot outline itself... areas I prefer not to discuss, because they are highly subjective and will differ from viewer to viewer. In this sense, the film becomes anything the viewer sees in it. If the film stirs the emotions and penetrates the subconscious of the viewer, if it stimulates, however inchoately, his mythological and religious yearnings and impulses, then it has succeeded.

I've quoted at length this highly revealing interview by Kubrick, given just after 2001 was released and which details his ambition and method for this film (and all subsequent films), so that we can conclude two things. Firstly, that the surface layer plot is little more than a vehicle for an effect or range of emotional effects that Kubrick wishes to provoke in the viewer - and we emphasise 'viewer' because this is above all a visual experience. And secondly, as he is attempting to communicate in this way, by means of poetic and mythological symbols, there is by nature a high degree of subjectivity and imprecision going on here.

That's to say, any attempt to pin down a precise allegorical meaning, where this character or plot element 'means' or 'represents' a particular concept, will be doomed to failure.

This relates to the first of two attempts to draw on Nietzsche's Thus Spoke Zarathustra as an explanatory framework for this film, Leonard F. Wheat's study Kubrick's 2001: A Triple Allegory (2000). His thesis is that 2001 is actually three separate allegories overlaid on each other, and underlying the surface narrative: Homer's Odyssey, a "Man Machine Symbiosis Allegory" and Nietzsche's Zarathustra.

Wheat is a PhD in political economy and a veteran economist in US government, but not a specialist in film or literature. This shows in his repeated assumption that a story must either be a) wholly realistic or else b) allegorical and symbolic. No other motivation for deviation from the strictly realistic, such as dramatical-structural, is considered by him. But any teller of fictional tales could inform him that thoughts of the most impactful moment to drop plot points, to withhold or reveal information to the audience, are always foremost.

Thus, a consideration by Wheat that it makes no sense for Heywood Floyd's NASA to keep the Discovery crew in the dark about the Jupiter signal, and that there's no good reason for the video briefing to be given right after HAL's death, concludes that the only reason for this illogical plot development is to be a symbolic indicator - that it's internally 'a plot hole', so therefore it must be a signpost towards an allegory. The idea that this is simply the best dramatic moment to reveal this information to Bowman and the audience, the mortal conflict between man and machine having just been resolved, just doesn't occur to him.

Another clear overreach comes when Wheat claims that Bowman's mismatched orange spacesuit and green helmet (after returning to the Discovery through the airlock) signify the sectarian violence of Ireland between Catholics and Protestants, and that therefore HAL, as a false God, must be killed. This is just absurd and silly.

And all very unnecessary, as the fundamental argument - at least in regard of Nietzsche's Zarathustra - rests on very solid ground. So much gilding the lily with extraneous and rather ridiculous detail doesn't help his case at all, but weakens it.

It also runs against the general purpose of Kubrick to create a mythical/preconscious channel of communication. A reference to something so local and esoteric as a conflict in Northern Ireland defeats that purpose. As someone saturated in that particular historical conflict, it would never occur to me, not even preconsciously, in witnessing this scene; instead the mismatched helmet just adds to the sense of unease along with the off-kilter camera work, wobbly and anxiety-generating, that goes with this 'murder scene'.

My own belief is that the Odyssey symbolism is present as a general signifier of what it means in general - a long and dangerous voyage with epic implications. Detailed allegorical parallels are clumsy and completely unnecessary. Bowman-as-Odysseus never returns to his Penelope, there is no Telemachus the faithful son or anything corresponding to the hero's homecoming. Moreover, the highly literate Kubrick would be well aware that James Joyce's Ulysses already created a contemporary narrative on the back of an Odyssey allegory. He would not want to repeat Joyce's feat.

Meanwhile Wheat's second strand, The Man-Machine Symbiosis and Conflict, is a clear thematic element of the film but likewise doesn't require detailed allegorical explication. Rather it folds into what I believe really is a core allegorical element, the Zarathustra myth as created by Nietzsche to symbolise his evolutionary theory of humanity, from animal-ape to higher man and on into the Übermensch or overhuman.

A second interpretation along these lines, by film scholar Jerold J. Abrams, doesn't fall into these very obvious traps of attempting to be too detailed and point-for-point, recognizing instead that Kubrick's allegorical substructure must be more general in order to work as intended.2

But it makes a more fundamental mistake in considering that the aliens are somehow a new god in this Kubrick mythology. This, I think, is absurd, and my belief is that Kubrick's interest in the alien intelligences is minimal and essentailly functional. They are something that move the plot forward, an extraterrestrial McGuffin. They have no significance in themselves.

By elimination, the fundamental conflict in this drama must be between man and machine, or human and artificial intelligence. As Wheat observes, the place of Nietzsche's God or false idol is taken by HAL, and it is this God that must be killed in order for the higher man (astronaut Bowman) to progress in becoming the overhuman or Übermensch (the final Starchild) - the “trans-human”.

What is the purpose of the mythology for Kubrick? It's to add a layer of depth to the emotional effect by being a 'message' that can be communicated by purely visual or symbolic means, without the need for explication or dialogue. Why choose Nietzsche's purely synthetic myth of the prophet Zarathustra and the New Man? Because it relates specifically to the evolution of the human into a new future stage of becoming.

What exactly that means in practice is not something that Kubrick wishes to explore in detail. It remains the suggestive but embryonic (pun intended) Starchild. But getting there does involve killing the dysfunctional artificial intelligence that threatens human values. A false idol, a God, that the 'higher men' of spacefaring technologists have set up in the place of the traditional Jehovah.

This is where the "highly subjective" interpretations of the viewer come into play: some will see the unseen aliens (mistakenly, I believe) as a type of immanent divinity, others will see the aliens as a form of advanced technology, possibly AI themselves, equivalent to a creator god but inhuman and material (this is the view of Abrams mentioned above), while others will stick closer to the view I've outlined: a mythical struggle between human and machine intelligence for supremacy within the context of progression to the next stage of conscious evolution, the “trans-human”.

To Kubrick, this interpretation is necessarily personal to the cinemagoer and unprogrammable: he, as director, cannot predetermine what it will be for each viewer. What he wants is for the viewer to become closely involved with, strongly affected by, the philosophical and spiritual issues he explores in his film. But he doesn't want you to think about those issues, he wants you to live them as vital life or death experiences.

— INTERMISSION —

For Part 2 (on Villeneuve’s Arrival) see HERE

Not coincidentally, this music was selected by the BBC as the theme for all their TV coverage of the Apollo missions to the Moon, so that a young me asssociated this music with the daring adventure of space exploration long before I finally go to see Kubrick's film in a 10th anniversary showing.

Jerold J. Abrams, “Nietzsche’s Overman as Posthuman Star Child in 2001: A Space Odyssey” in Abrams, Jerold J. (ed), The Philosophy of Stanley Kubrick (2008)

super interesting breakdown. I watch 2001 from time to time to 'watch' it, and considering your thoughts here, I will probably still just watch it, but maybe a little differently now. So thank you.